In the annals of automotive history, certain vehicles stand as testaments to ambition, engineering prowess, and the relentless pursuit of speed. The Mercedes-benz T80, also known as Type 80, is undoubtedly one such machine. Conceived in the late 1930s amidst the fervor of pre-war Germany, this colossal six-wheeled vehicle was designed not just to break the world land speed record, but to shatter it in a display of national technological dominance. Driven by the vision of German auto racer Hans Stuck and fueled by the propaganda ambitions of Adolf Hitler, the T80 project brought together some of the most brilliant minds in German engineering, including Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, to create a vehicle unlike any other. Though it never achieved its intended record run due to the outbreak of World War II, the Mercedes-Benz T80 remains a captivating artifact, a symbol of a dream deferred, and a remarkable example of automotive engineering pushed to its absolute limits.

The Vision of Speed and Propaganda

The Mercedes-Benz T80 project was born from the ambition of Hans Stuck, a renowned German racing driver who dreamt of capturing the world land speed record. In the politically charged atmosphere of the late 1930s, Stuck successfully pitched his vision to Wilhelm Kissel, the Chairman of Daimler-Benz AG, convincing him to undertake the development and construction of a record-breaking vehicle. Crucially, Stuck also secured the backing of Adolf Hitler, who saw the land speed record as a potent propaganda tool to showcase Germany’s supposed technological superiority on the global stage.

Initially, Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, tasked with designing the vehicle, targeted a speed of 342 mph (550 km/h), anticipating an engine output of 2,000 hp (1,490 kW). However, as other nations began pushing the boundaries of land speed records, the target for the T80 was progressively raised. With advancements in engine technology and the escalating international competition, the goal was revised upwards. By 1939, as the T80 neared completion, the ambitious target speed for its record attempt was set at a staggering 373 mph (600 km/h), to be achieved after a 3.7 mi (6 km) acceleration run. This escalating ambition reflected not only the technological race of the era but also the growing political pressure to demonstrate German preeminence.

Engineering Marvel of the 1930s

The Mercedes-Benz T80 was not just about brute force; it was a meticulously engineered machine, pushing the boundaries of aerodynamics and automotive technology of its time. The project, which ultimately cost 600,000 Reichsmarks (approximately $4 million USD today), was a testament to the dedication and ingenuity of German engineers and designers.

Aerodynamic Design and Bodywork

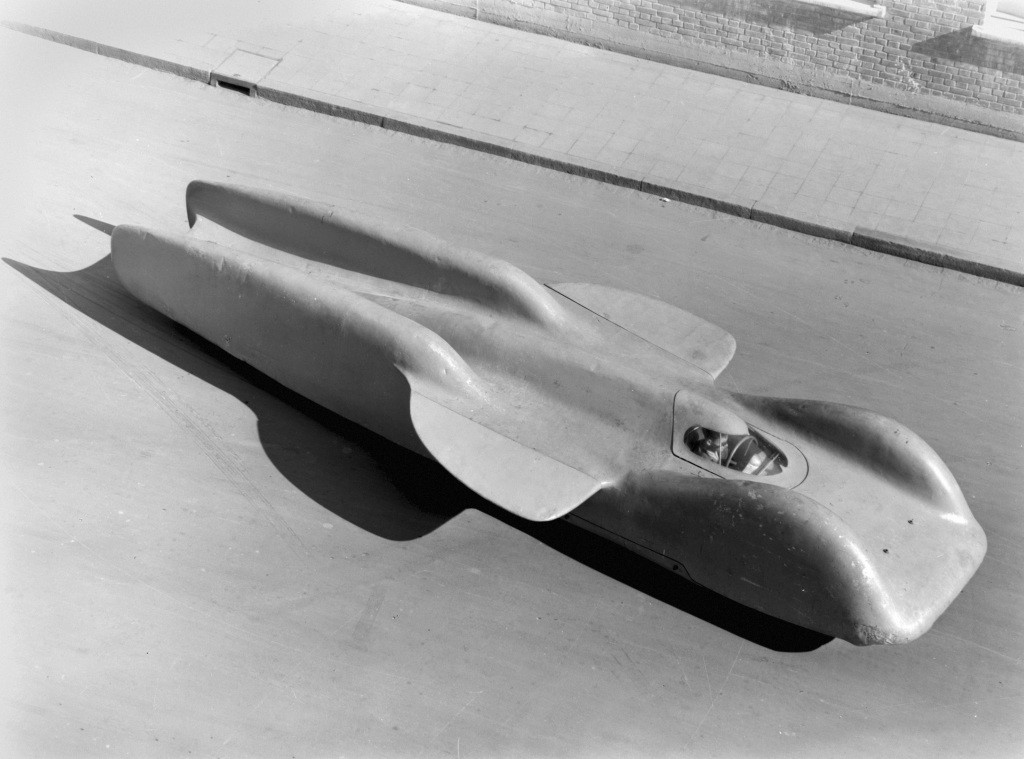

To achieve the targeted speeds, aerodynamics became paramount. Mercedes-Benz enlisted the expertise of Josef Mikcl, an aerodynamics specialist, to streamline the T80’s body. The bodywork itself was constructed by aircraft manufacturer Heinkel Flugzeugwerke, leveraging their expertise in lightweight and aerodynamic structures. The T80 incorporated a Porsche-designed enclosed cockpit, a low-sloping hood to minimize frontal area, and gracefully rounded fenders to reduce drag. Notably, the rear wheels were encased within elongated tail fins, a crucial design element intended to stabilize the vehicle at high velocities. Further enhancing stability and downforce were two small wings positioned at the mid-section of the car. These combined aerodynamic features resulted in an exceptionally low drag coefficient of just 0.18, a figure that remains impressive even by modern standards, highlighting the advanced aerodynamic thinking incorporated into the T80’s design nearly a century ago.

The Powerhouse: DB 603 Aircraft Engine

At the heart of the Mercedes-Benz T80 lay a formidable engine – a 2,717 cu in (44.5 L) Daimler-Benz DB 603 inverted V-12 aircraft engine. This powerplant, typically found in high-performance aircraft, was chosen to deliver the immense power required to propel the T80 to record-breaking speeds. Ernst Udet, a key figure in Germany’s Aircraft Procurement and Supply, facilitated the acquisition of the third DB 603 prototype engine for installation in the T80, underscoring the project’s national importance.

The DB 603 engine destined for the T80 was not a standard aircraft engine. It was a specially tuned, supercharged variant with mechanical fuel injection, meticulously engineered to produce a staggering 3,000 hp (2,240 kW). This immense power output was achieved through a combination of advanced engineering and a specialized high-performance fuel mixture. This exotic fuel comprised methyl alcohol (63%), benzene (16%), ethanol (12%), acetone (4.4%), nitrobenzene (2.2%), avgas (2%), and ether (0.4%). To further enhance performance and prevent engine knocking, the engine utilized MW (methanol-water) injection for charge cooling and anti-detonation, showcasing the cutting-edge engine technology employed in the T80 project.

Drivetrain and Traction Control

Transmitting the immense power of the DB 603 engine to the wheels required a robust and sophisticated drivetrain. The T80 employed a hydraulic torque converter to channel power from the engine to a single-speed final drive, which in turn distributed power to the four driven rear wheels across two axles. Given the immense power and the challenges of maintaining traction at extreme speeds, the T80 was equipped with a mechanical “anti-spin control” device. This innovative system utilized sensors on both the front and rear wheels to detect wheel spin. If the rear wheels began to rotate faster than the front wheels, indicating a loss of traction, the system would automatically reduce fuel flow to the engine, thus mitigating wheel spin and enhancing stability – a pioneering example of traction control technology in its era.

Dimensions and Specifications

The sheer scale of the Mercedes-Benz T80 was as impressive as its engineering. The vehicle measured a substantial 26 ft 8 in (8.128 m) in length and stood 4 ft 1 in (1.245 m) tall. Its body width was 5 ft 9 in (1.753 m), and with the inclusion of its stabilizing wings, the total width expanded to 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m). All six wheels were of size 7 in x 32 in and had a track width of 4 ft 3 in (1.295 m). Despite its massive dimensions, the T80 was relatively lightweight for its size, weighing in at approximately 6,390 lb (2,900 kg), a testament to the advanced construction techniques and materials used.

The Black Bird and the Autobahn Run

The Mercedes-Benz T80 was unofficially christened “Schwarzer Vogel” (Black Bird) by Adolf Hitler, reflecting its imposing appearance and perhaps its intended dominance. In line with the nationalistic fervor of the time, the vehicle was intended to be painted in German national colors, complete with the German Eagle and Swastika emblems, further emphasizing its role as a symbol of national pride and technological might.

The planned location for the record attempt was a specially prepared stretch of the Dessau Autobahn (part of the modern A9 Autobahn). This section of the Autobahn was widened to 82 ft (25 m) and extended for 6.2 mi (10 km), with the median strip paved over to create a wide, smooth surface suitable for high-speed runs. Hans Stuck was designated as the driver for the record attempt, which was initially scheduled for January 1940. This event was intended to be the first absolute land speed record attempt ever undertaken in Germany, adding to its national significance.

War Intervenes and a Dream Deferred

Tragically, the ambitious land speed record attempt of the Mercedes-Benz T80 was thwarted by the outbreak of World War II in September 1939. The escalating global conflict brought the project to an abrupt halt just as it was nearing completion. The final touches on the T80 were never fully realized, and the vehicle never had the opportunity to run under its own power, its immense potential remaining untapped.

Following the cancellation of the record attempt, the T80 was placed in storage. In late February 1940, the valuable DB 603 engine was removed, likely for wartime applications, and the T80 chassis was relocated to Karnten, Austria, where it remained safely stored throughout the duration of the war. For many years, the Mercedes-Benz T80 remained largely unknown outside of Germany, its existence shrouded by the secrecy of wartime and the shifting global landscape.

Post-War Discovery and Legacy

The Mercedes-Benz T80 emerged from obscurity after World War II when it was discovered by the Allied forces. Remarkably, the vehicle had survived the war relatively unscathed, a testament to its careful storage and perhaps a symbol of forgotten ambitions amidst the global upheaval. Recognizing its historical and engineering significance, the T80 was eventually moved to the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, Germany.

Today, the Mercedes-Benz T80 stands as a prominent exhibit in the museum’s “Silver Arrows – Races & Records Legend” room, captivating visitors from around the world. While the chassis is currently in storage at a museum warehouse, the body of the T80 is on permanent display, allowing enthusiasts and historians alike to marvel at its imposing form and groundbreaking design. The T80 serves as a powerful reminder of the audacity of pre-war automotive engineering and the dreams that were interrupted by the tides of history.

What Could Have Been: The T80’s Potential

Although the Mercedes-Benz T80 never had the chance to prove its capabilities on a record run, estimates of its potential top speed are truly astonishing. Following its discovery after the war, Allied engineers were quoted an estimated top speed of 465 mph (750 km/h) for the T80. Had the T80 been capable of achieving this estimated velocity, it would have established a land speed record that would have remained unbroken until 1964, when Craig Breedlove surpassed it in the jet-powered “Spirit of America” at 468.72 mph (754.33 km/h).

Even more significantly, the Mercedes-Benz T80 would still hold the distinction of being the fastest piston-engined, wheel-driven vehicle ever created. This enduring claim underscores the T80’s unique place in automotive history, not just as a machine of immense power and speed, but as a pinnacle of piston-engine technology in the pursuit of land speed records. The T80 remains a tantalizing “what if” in the history of speed, a testament to a dream that, while never fully realized, continues to inspire awe and fascination.

The Key Players Behind the Project

The Mercedes-Benz T80 project was the brainchild of racing driver Hans Stuck, fueled by his ambition to break the absolute world land speed record. To bring this ambitious project to fruition, Stuck enlisted the support of three key figures: Wilhelm Kissel, Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler-Benz AG; the brilliant engineer Ferdinand Porsche; and air force general Ernst Udet. Each of these individuals played a crucial role in the development of the T80 during the 1930s.

Stuck’s initial contact with Porsche came through their shared history with Auto Union, where Porsche had designed the successful Grand Prix racing cars. Ernst Udet, who Stuck knew from ice racing events in the 1920s, proved instrumental in securing the necessary aircraft engine from the Ministry of Aviation. Wilhelm Kissel, recognizing the potential prestige and propaganda value, provided Daimler-Benz’s resources and engineering expertise to the project. This collaboration of racing ambition, engineering genius, and political backing formed the foundation for the Mercedes-Benz T80 endeavor.

Development and Challenges

The development of the Mercedes-Benz T80 was a marathon undertaking, spanning from its initial conception in 1936 to its premature end in 1940. The project progressed through numerous development stages and vehicle refinements, constantly adapting to evolving speed targets and technological challenges.

Early on, the selection of the engine was a critical decision. While initial plans considered the DB 601 aircraft engine, the escalating speed goals necessitated a more powerful powerplant, leading to the adoption of the larger and more potent DB 603. Tyre technology also presented a significant hurdle. Tests conducted by Continental revealed severe deformation of the initially chosen wire-spoked wheels at high speeds, requiring further development and refinement to ensure tyre integrity at the projected velocities.

Wind tunnel testing at the Zeppelin company in Friedrichshafen played a crucial role in optimizing the T80’s aerodynamics. Engineers sought to achieve the ideal balance of downforce – sufficient to maintain traction but minimal enough to avoid excessive stress on the tyres. These tests led to modifications, including a reduction in the surface area of the downforce fins, demonstrating the iterative and data-driven approach to the T80’s design.

Financing the ambitious project was also a complex undertaking. Daimler-Benz agreed to cover the chassis construction costs, while aircraft manufacturer Heinkel was initially slated to build and finance the body. Hans Stuck himself was expected to organize and fund the record-breaking attempt, highlighting the collaborative and multifaceted nature of the T80 project.

Despite the immense effort and resources invested, the Mercedes-Benz T80 project ultimately fell victim to the outbreak of World War II. The war not only halted the record attempt but also brought an end to the further development of this extraordinary machine, leaving it as a remarkable, yet unrealized, chapter in automotive history.

OFFICIAL PRESS RELEASE

The Mercedes-Benz T 80 world record project car was the brainchild of racing driver Hans Stuck: he wanted to break the absolute world land speed record. Stuck completed the project with the help of three major personalities: Wilhelm Kissel, the Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler-Benz AG, engineer Ferdinand Porsche and air force general Ernst Udet. During the 1930s each of them made their contribution to completion of the project. The story of the Mercedes-Benz T 80 is a marathon for the designers and aerodynamicists: the project began in 1936. Via numerous development stages and vehicle refinements, it came to an end in 1940 – without the T 80 ever being used.

The aim of all those involved was to achieve a speed never before reached by any land vehicle. This was all the more challenging because, in that period, British drivers were establishing new records all the time at Daytona Beach and on the Bonneville Salt Flats: on 3 September 1935, Malcolm Campbell reached a speed of 484.62 km/h over the flying mile with “Blue Bird”. On 19 November 1937, George Eyston broke the 500 km/h barrier with “Thunderbolt” (502.11 km/h over the flying kilometre). And finally on 23 August 1939, John Cobb established a new record of 595.04 km/h over the flying kilometre with “Railton Special”. Accordingly the planned target speed of 550 km/h was revised upwards, first to 600 km/h and finally even to 650 km/h.

A new record for the Silver Arrows

If this project proved successful, Mercedes-Benz would add another triumph to a long list of speed records. The highlight to date was the speed record on public roads established by Rudolf Caracciola on 28 January 1938: he reached a speed of 432.7 km/h with the record-breaking Mercedes-Benz W 125 on the autobahn near Darmstadt. Nevertheless, the T 80 project was not without its critics within the company. This was not least due to Hans Stuck himself. After all, the Grand Prix racing driver competed for Auto Union in the 1930s. How would the public respond if the highly successful Stuttgart racing department engaged a driver from the competition for its absolute world record attempt? Many decision-makers in the company therefore wondered if it would not be better to entrust works driver Rudolf Caracciola with the record-breaking attempt as previously.

On the other hand, Stuck also had connections with the Stuttgart brand: in 1931 and 1932, driving a Mercedes-Benz SSKL, he raced very successfully for the Mercedes star. In 1932 he became international Alpine champion and Brazilian hill-racing champion. Four years later, Stuck was now using his former contacts with Untertürkheim.

Via the racing department of Auto Union, he made contact with designer Ferdinand Porsche. It was on the latter’s P-vehicle concept that the Grand Prix racing cars of Auto Union were based from 1934 to 1936. And flying ace Ernst Udet had already known Stuck since the 1920s. At that time the two would spar off, e.g. in ice races on the frozen Lake Eib near Garmisch-Partenkirchen: Stuck driving an Austro Daimler racing car and Udet flying an aircraft.

Telegram to Stuttgart

What was the motivation for Stuck’s desire to break the absolute world land speed record? One reason was undoubtedly his Auto Union team mate Bernd Rosemeyer. When the latter won the European Grand Prix championship in 1936, Hans Stuck started looking for another stage on which to demonstrate his driving skills. An obvious possibility was the world record, which was dominated by British drivers at the time.

Stuck had contacts in the National Socialist government, and knew that he could rely on political support for this prestige project. Nonetheless, he also needed partners for its technical implementation. On 14 August 1936 he sent a telegram from Pescara to the Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler-Benz, Wilhelm Kissel, requesting a meeting. In a conversation with Kissel, the racing driver suggested that Mercedes-Benz should build a record-breaking vehicle powered by a Daimler-Benz aircraft engine. The British record-breaking cars of that era were also powered by aircraft engines.

Record-breaking attempts were not new territory for Mercedes-Benz. After all, the Stuttgart-based company had set numerous records in the 1930s. And as Kissel remembered, the idea of building a record-breaking vehicle powered by an in-house aircraft engine had already come up under the aegis of late Daimler-Benz board member Hans Nibel, who died in 1934.

The vehicle for the record attempt was to be designed by Ferdinand Porsche, who had left his position as Chief Engineer at Mercedes-Benz in 1928. However, there were still connections between the world’s oldest automobile manufacturer and the Porsche design studio (P.K.B.). Between 1936 and 1937 Mercedes-Benz, among other things, built 30 prototypes of the “KdF” car, which went into series production as the VW Beetle after the Second World War.

On 11 March 1937, Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche GmbH concluded a contract with Daimler-Benz AG for extensive involvement in all areas of engine and vehicle design. As well as the T 80 (according to Porsche nomenclature, the “T” stood for “type”), the resulting projects included the T 90, T 93, T 94, T 95, T 97, T 104 and T 108. So, in addition to the world record project vehicle, Porsche was also involved in developing racing cars, commercial vehicles and engines.

An aircraft engine for a world record

The T 80 was to be powered by a Daimler-Benz aircraft engine. However, the manufacturer did not have automatic access to such a unit, as the Ministry of Aviation had sole rights of disposal over all aircraft engines produced in Germany. Therefore, Stuck put his connection with Ernst Udet to good use. The flying ace had meanwhile been promoted to head of the Luftwaffe’s technical department.

Fritz Nallinger, at that time Daimler-Benz’s technical director responsible for the design, development and production of large engines, commented on the project in September 1936. In Nallinger’s estimation, an output of 1,103 kW (1,500 hp) with the initially proposed DB 601 aircraft engine was definitely possible. In fact, 2,036 kW(2,770 hp) was achieved with a version of this engine prepared for flying record attempts in 1938 and 1939.

In October 1936 Kissel informed Porsche by telephone that the Ministry of Aviation was willing to release two engines. He also asked Porsche to commence work on the project. The official order followed on 13 January 1937. An appendix to the order pointed out that the Porsche design was always only to be referred to as a Mercedes-Benz world record project vehicle.

The financing was initially arranged as follows: Daimler-Benz would bear the cost of building the chassis. The body was to be built and paid for by aircraft manufacturer Heinkel. Organisation of the record-breaking attempt itself would be financed by racing driver Stuck himself. This had already been laid down by Kissel when he met with Stuck on 21 October 1936. In November 1936 Kissel estimated that the T 80 could not be completed before October 1937.

In February 1937, the project took a major step forward when Ernst Udet approved the official release of the DB 601 aircraft engine for installation in the T 80. In view of the greater power requirement that became obvious during the course of development, this approval was later extended to the DB 603 V3.

On 6 April Porsche presented his plans for the T 80 in Untertürkheim. These describe a multistage development process, from an initial twin engine proposal to a final single engine concept. This latest proposal already showed most of the characteristics of the vehicle actually built: a three-axle record-breaking car powered by a centrally suspended V12 aircraft engine. Porsche calculated that for a record speed of 550 km/h after a distance of five kilometres, an engine output of at least 1,618 kW (2,200 hp) or better still 1,838 kW (2,500 hp) would be necessary.

Originally the plan was to use a track in the United States of America for the record-breaking attempts. In mid-1938 this gave way to a plan to use a specially prepared section of the autobahn between Dessau-South and Bitterfeld instead. In August 1938 the General Inspector of German Roads, Fritz Todt, announced that the date for the proposed release of this autobahn section for use would be in October 1938.

The question of the location for the record attempt was never actually settled. But there was still talk of a record attempt in the USA in 1939. All the world speed records of recent years had been achieved on the Bonneville Salt Flats in the USA. One reason for the renewed discussion at Mercedes-Benz might have been the difficult driving conditions on the manually paved median between the two lanes on the envisaged section of the autobahn.

The birth of the world record car

The T 80 increasingly took shape during the course of 1938. In October Ferdinand Porsche viewed the wooden model of the bodyshell together with employees. It was now time to define the types of steel panelling for the body and produce a corresponding bill of materials, decide on the details of the seat and cockpit and formulate the tubular structure of the spaceframe. On 26 October 1938, the Mercedes-Benz racing department recorded in a test report that the first welded frame weighed 224 kilograms.

The chassis and frame were completed at the end of November 1938. The Mercedes-Benz racing department planned that the vehicle complete with all its major assemblies would be ready by the end of January 1939. A memo dated 26 November 1938 states that if the aircraft engine could also be delivered by then, the chassis could be assembled by the end of February 1939. The body would then be completed by May 1939.

Will the tyres withstand the record-breaking speed?

Tyre manufacturer Continental tested the wheels intended for the T 80 on a test stand, and during a high-speed test at 500 km/h in January 1939 found severe deformation of the wire-spoked wheels supplied by Hering in Ronneburg (Thuringia). In May there were still slight deformations at 480 km/h. Porsche had meanwhile calculated that a distance between 13.73 kilometres (with 2,023 kW/2,750 hp) and 11.48 kilometres (with 2,206 kW/3,000 hp) would be necessary for a record-breaking run at 600 km/h.

In 1939 the decision was reached to equip the T 80 with a DB 603 engine. In March 1937 the Ministry of Aviation had forbidden its further development as an aircraft engine, but it could be used for the land speed record if the ministry approved. The engineers were confident that the 44.5-litre V12 aircraft engine designed for an output of around 1,471 kW (2,000 hp) could reach up to 2,206 kW (3,000 hp) at 3,200 rpm during a record-breaking attempt. To this end the engine was to be fuelled with the two special racing fuels XM and WW. From February 1940 the company was permitted to restart its work on the DB 603 as an aircraft engine. Series production for aviation use began in 1941.

Optimisation of the DB 603 for the record attempt

In 1939 racing manager Alfred Neubauer noted down that a DB 603 for the T 80 could be delivered as a “running-in engine” in June of that year. The engine to be used in the actual record attempt would be available at the end of August 1939. In June Fritz Nallinger, who was responsible for Daimler-Benz aircraft engines, improved various details for installation of the world record project engine in the T 80. This included modifying the routing of the air intake ducts and configuring the exhaust ducts so that the vehicle could convert recoil energy into speed.

In summer 1939 measurements on a scale model of the T 80 were also carried out in the wind tunnel of the Zeppelin company in Friedrichshafen. The aim was to find the optimum level of downforce: strong enough to bring the entire engine power onto the road, but as low as possible so as not to overload the tyres with their thin tread surfaces. Following these measurements, the surface area of the downforce fins was reduced by another 3.65 square metres.

Testing of the T 80 was also continued after the outbreak of the Second World War on 1 September 1939. On 12 October the chassis of the world record project car was tested on the roller dynamometer, for example. In view of the new record of almost 600 km/h set by Cobb, Porsche was meanwhile envisaging a speed of up to 650 km/h for the record-breaking attempt. This would probably make an engine output of up to 2,574 kW(3,500 hp) necessary. Even this level of power seemed possible with the DB 603.

End of the T 80 project in spring 1940

No further steps were taken towards achieving the world land speed record. As early as February 1940, Mercedes-Benz sent an enquiry to the Ministry of Aviation about a possible contribution towards the development and production costs. In June 1940 a final report was produced for the project, and the T 80 was placed in storage. The DB 603 world record project engine meanwhile installed in the vehicle was returned to the Ministry of Aviation.

After the Second World War, Mercedes-Benz exhibited the T 80 in the company’s museum in Untertürkheim. When the museum was reorganised in 1986, the body and chassis were separated and the chassis was placed in storage. The new Mercedes-Benz Museum opened in 2006 outside the gates of the Untertürkheim plant also presented the T 80 in the permanent exhibition with its original body, spaceframe and wheels – but without the heavy chassis.

The body exhibited in the Mercedes-Benz Museum intentionally shows the world record project car with traces of the project work which was unfinished in 1940. Mercedes-Benz Classic is now juxtaposing the chassis together with the replicated spaceframe and the cutaway engine with this mighty exhibit. From mid-2018 this unique exhibit will make the technology of the T 80 immediately and impressively accessible.

SaveSave

SaveSave

More: Autos, Mercedes-Benz, Classic