1. Introduction

Benzodiazepines (BZDs), initially hailed as a safer alternative to barbiturates, are widely prescribed for conditions like anxiety and insomnia. They work by enhancing the effects of GABA, a neurotransmitter that calms brain activity. However, despite their therapeutic benefits, BZDs carry risks, including side effects like drowsiness and the potential for dependence. Recognizing this abuse potential, international bodies have scheduled many common BZDs under controlled substance conventions. This regulation, however, has inadvertently fueled the rise of designer benzodiazepines (DBZDs), also known as novel benzodiazepines or new psychoactive substances (NPS).

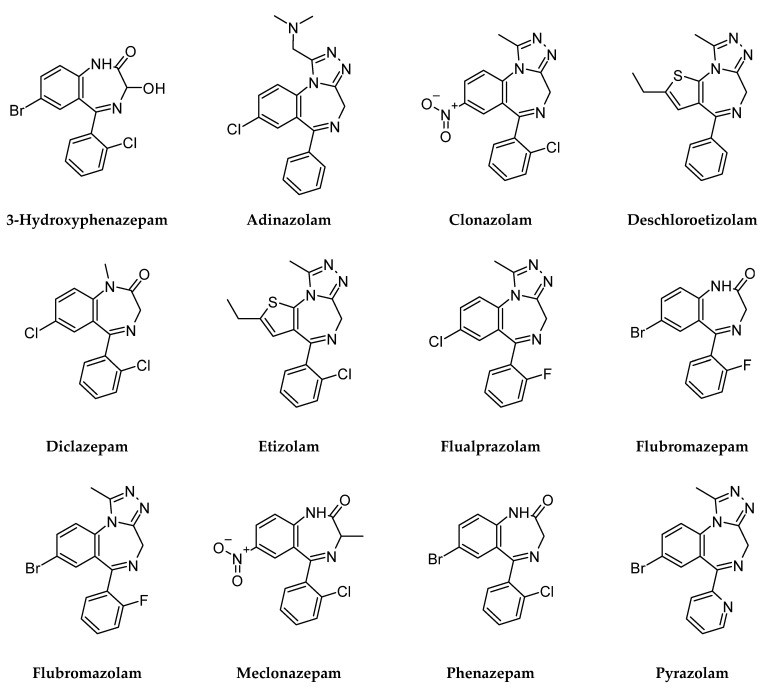

Designer Benzos are structurally similar to traditional benzodiazepines but are often modified to circumvent legal restrictions. This category includes substances not yet formally controlled, those marketed in specific regions only, and even metabolites of regulated BZDs. These designer drugs present a significant challenge to public health and law enforcement due to their rapidly evolving nature and unpredictable effects. Slight alterations to the core BZD structure create a wide array of compounds, primarily within the 1,4-benzodiazepine, triazolobenzodiazepine, and thienotriazolodiazepine families. The latest designer versions often incorporate triazolo rings and electron-withdrawing groups, which can significantly boost their potency at GABA receptors.

Compared to classic benzodiazepines, designer benzos are often reported to induce more intense sedation and amnesia. Crucially, they amplify the risk of respiratory depression and fatal overdose, especially when combined with other central nervous system depressants like opioids or alcohol. Adding to the danger, most designer benzos have not undergone rigorous clinical testing, leaving their long-term effects, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity largely unknown. Information is often limited to user reports and emerging toxicology data. These substances are frequently manufactured illegally in clandestine labs, sometimes mimicking legitimate pharmaceuticals, and are easily accessible through online platforms, bypassing regulatory oversight. Early examples identified online in Europe include phenazepam and nimetazepam, followed by etizolam. While not strictly “designer” as they have some medical use, their abuse contributed to the growing DBZD problem. Pyrazolam, identified in Finland, was one of the first truly “designer” benzos with no prior medical approval. To date, numerous distinct designer benzos have been reported, predominantly in Europe, with bulk materials often originating from Asia and then processed and sold illicitly, sometimes misrepresented as counterfeit versions of drugs like alprazolam (Xanax) or nimetazepam (Erimin-5).

The non-medical use of designer benzos, frequently alongside other drugs, is a growing global health crisis. Seizures and undercover purchases in the US have dramatically increased, highlighting their escalating prevalence. During periods of classic drug shortages, such as during COVID-19 restrictions, some users have shifted to designer benzos and novel synthetic opioids. The clandestine production of designer benzos means they lack quality control and may contain variable dosages or dangerous contaminants, including potent opioids and other NPS. Users are often unaware of these risks, leading to a surge in adverse health events, emergency room visits, and fatalities. Furthermore, designer benzos are increasingly implicated in impaired driving and traffic accidents. Data indicates a significant presence of designer benzos in post-mortem and driving under the influence of drugs (DUID) cases, with substances like flualprazolam, flubromazolam, and etizolam being frequently detected.

Recognizing the severe abuse potential and life-threatening consequences, international authorities have moved to control several designer benzos, including clonazolam, diclazepam, etizolam, flualprazolam, and flubromazolam, by adding them to Schedule IV of the Convention of Psychotropic Substances. This review aims to provide an updated overview of emergency department admissions, DUID incidents, and post-mortem investigations involving designer benzos. The goal is to offer current toxicology and epidemiological data to inform public health strategies and improve safety measures related to designer benzo use.

Figure 1: Chemical Structures of Designer Benzodiazepines. This image illustrates the structural variations in common designer benzodiazepines, highlighting the core benzodiazepine structure and common modifications.

2. Case Review: Designer Benzo Incidents

From an initial pool of 372 reports, 49 were selected that specifically detailed emergency department (ED) admissions, driving under the influence of drugs (DUID) incidents, or fatalities directly linked to designer benzodiazepine (DBZD) use. Reports lacking these criteria or focusing on DBZDs without sufficient data (like 4-chlorodiazepam and others listed in the original article) were excluded. Twelve DBZDs emerged as significant in the included reports: 3-hydroxyphenazepam, adinazolam, clonazolam, etizolam, deschloroetizolam, diclazepam, flualprazolam, flubromazepam, flubromazolam, meclonazepam, phenazepam, and pyrazolam. These substances were implicated as the primary or contributing cause in cases of poisoning, impaired driving, and death. This review summarizes 254 cases reported between 2008 and 2021, encompassing 1 drug offense, 2 self-administration studies, 3 outpatient department admissions, 44 ED admissions, 63 DUID incidents, and 141 fatalities, all detailed in Table 1 of the original article. This data includes patient demographics, observed symptoms, drug concentrations in biological samples, and substances co-administered with DBZDs.

The affected individuals were predominantly young adults, both male and female, often with pre-existing substance abuse issues or mental health conditions. Designer benzo-related emergencies and deaths occurred across various countries, including Finland, Germany, Japan, Norway, Poland, Sweden, the UK, and the USA. Analytical methods for DBZD detection included LC-HRMS (LC-QTOF-MS and LC-Orbitrap-MS) for screening and LC-MS, LC-MS/MS, LC-DAD, GC-MS, or GC-MS/MS for quantification.

2.1. Adinazolam

Adinazolam, a triazolobenzodiazepine, is known for its anxiolytic, antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and sedative properties. Though never approved by the FDA, it surfaced as an illicit designer drug around 2015. Clinical studies showed that even moderate doses can cause drowsiness and dizziness, with higher doses leading to significant amnesia and impaired motor skills. The first reported fatality linked to adinazolam involved a young woman found deceased with bags of unidentified substances. Since 2020, US toxicology reports have linked adinazolam to deaths also involving etizolam, fentanyl, and flualprazolam. These cases involved individuals aged 20-40 in Michigan, Mississippi, and Rhode Island. While adinazolam was detected in post-mortem blood, it was not quantified or listed as the primary cause of death in these initial reports.

2.2. Clonazolam

Clonazolam, a potent analogue of clonazepam, is known for its intense sedative and amnesic effects, even at very low doses (as little as 0.5 mg). This potency increases the risk of accidental overdose. First identified in Sweden in 2014, it quickly became a concern in the designer benzo market. Case reports detail emergency department admissions following clonazolam use purchased online. Symptoms mainly involved central nervous system (CNS) depression. In some cases, clonazolam was found alone, while in others, it was detected alongside etizolam. Dosage in some ED cases was estimated based on patient self-reports.

2.3. Deschloroetizolam

Deschloroetizolam is structurally similar to etizolam but lacks a chlorine atom, resulting in reduced potency. It was first reported in the UK in 2014 after being identified in seized tablets. Data on deschloroetizolam is limited. A self-experiment documented significant behavioral changes and cognitive impairment after a 6mg dose. In a fatality case, deschloroetizolam and metabolites of diclazepam were found in a young man who died with drug paraphernalia and bags of various designer benzos, suggesting polysubstance abuse.

2.4. Diclazepam

Diclazepam, a derivative of diazepam, emerged in Europe around 2013. Emergency department cases involving diclazepam often presented with severe agitation and disorientation, frequently in combination with stimulants and dissociatives. In one ED case, diclazepam was the sole substance reported, with symptoms including CNS depression and withdrawal. The patient reported ingesting a large dose (240mg) purchased online. DUID cases involving diclazepam showed varying levels of impairment. Some drivers exhibited clear impairment in clinical tests, while others with similar blood concentrations showed no apparent impairment, highlighting the variability in individual responses and tolerance. One death was reported in a young man with a history of methamphetamine use who also used etizolam, with diclazepam and flubromazolam found post-mortem along with opioids and stimulants, indicating polydrug use as a likely factor in the fatality.

2.5. Etizolam

Etizolam, a thienotriazolodiazepine, is approved for medical use in some countries like India, Italy, Japan, and Korea for short-term treatment of anxiety and insomnia, but not in many others. It was first flagged as a substance of abuse in the UK in 2011. Emergency department admissions include cases of children accidentally ingesting etizolam pills mistaken for candy. Adult cases include overdoses and withdrawal syndromes, with some individuals using it for self-detoxification from other substances. DUID cases show etizolam causing motor and functional impairment in drivers. Fatalities linked to etizolam are significant. Many are accidental overdoses due to polydrug use, often in individuals with substance use disorders or mental health issues. However, etizolam has also been implicated in suicides. Blood concentrations of etizolam in fatalities vary widely, and it is not always listed as the primary cause of death in polydrug toxicity cases.

2.6. Flualprazolam

Flualprazolam, an analogue of alprazolam, was first reported in Sweden in 2018. Emergency department cases include young people experiencing sedation, impaired speech, and CNS depression after ingesting substances believed to be alprazolam. DUID cases are numerous, with drivers showing considerable motor and functional impairment. Fatalities associated with flualprazolam are frequently linked to polydrug use and accidental overdose. While most deaths are accidental, some intentional poisonings have been reported. Flualprazolam blood concentrations in fatalities vary, and in many cases, it is not listed as the primary cause of death but rather as a contributing factor in polydrug toxicity.

2.7. Flubromazepam

Flubromazepam was first detected in Germany in 2013. Emergency department admissions involve patients with agitation, delirium, rigidity, and CNS depression. In one ED case, methoxyphenidine appeared to counteract some of flubromazepam’s depressant effects. DUID cases are less frequent, with one driver showing mild impairment. A single fatality case details a young man who died after days in the hospital following severe CNS depression. Flubromazolam and U-47700 were also detected and listed as causes of death, suggesting a complex polydrug toxicity scenario.

2.8. Flubromazolam

Flubromazolam, a triazolobenzodiazepine related to flubromazepam, emerged in Sweden in 2014. It’s known for strong and long-lasting CNS depressant effects. Emergency department cases frequently involve severe CNS depression and motor impairment. In most ED cases, flubromazolam was the only drug detected, while in some, meclonazepam was also present. DUID cases are common, with drivers showing significant motor and functional impairment. Fatalities have been reported, with flubromazolam listed as a contributing cause in some. Self-administration studies confirm its potent sedative and memory-impairing effects, even at low doses (0.5mg).

2.9. Meclonazepam

Meclonazepam, similar to clonazepam, was first reported in Sweden in 2014. Emergency department cases include individuals with agitation and non-reactive pupils after ingesting large quantities (e.g., 600mg). Patients are often awake but confused and not fully lucid.

2.10. Phenazepam and 3-Hydroxyphenazepam

Phenazepam, developed in the 1970s, has been used in some former USSR countries for anxiety, insomnia, and alcohol withdrawal. It was reported in Europe around 2011. Its active metabolite, 3-hydroxyphenazepam, has also been detected in illicit drug markets. Emergency department cases involve patients with motor and functional impairment and CNS depression. DUID cases are frequent, with drivers exhibiting moderate to considerable impairment. Fatalities are numerous, with phenazepam listed as the sole cause of death in some cases, but more often as a contributing factor in polydrug toxicity. However, some DUID cases show drivers with phenazepam in their system not exhibiting impairment, potentially due to tolerance.

2.11. Pyrazolam

Pyrazolam, a triazolobenzodiazepine, was first identified in Finland in 2012. One fatality case involved a young man found deceased with bags of pyrazolam and other substances. Polydrug intoxication leading to asphyxia was determined as the cause of death.

3. Discussion: The Growing Designer Benzo Crisis

Designer benzodiazepines are a rapidly expanding public health threat, particularly in Europe, which accounts for a large percentage of global seizures. Key DBZDs driving this crisis include clonazolam, diclazepam, etizolam, flualprazolam, flubromazolam, and phenazepam. Etizolam stands out as a particularly problematic “street” benzo, increasingly implicated in drug-related deaths. The problem is not confined to Europe; designer benzos are a growing concern in the US and are emerging in Central and South America. Surprisingly, data from Asia, the primary source of many NPS, remains limited.

The high public health risk associated with etizolam, flualprazolam, flubromazolam, and phenazepam is underscored by their widespread availability online in various forms (blotters, liquids, pills, powders, tablets) and at low prices. Etizolam and phenazepam are sometimes diverted from regulated markets or illegally imported from countries where they are legally prescribed. While international control measures typically reduce the availability of NPS, designer benzos like flualprazolam, phenazepam, flubromazolam, and etizolam have persisted in illicit markets for extended periods after initial alerts, leading to prolonged social harms. These harms include rising DBZD-related deaths, criminal activity, violence, risk-taking behaviors, suicide attempts, and polysubstance abuse.

This review focused on cases where DBZDs were a sole or contributing factor in adverse events to better understand their direct impact and biological concentrations in different scenarios. A key challenge is that clinicians may be unaware of designer benzos, potentially misinterpreting overdoses and deaths. Enhanced awareness and routine screening for NPS and DBZDs in clinical settings are crucial. Patients themselves may be unaware of the substances they are consuming, further complicating the issue. Analyzing cases where a DBZD is the only substance detected helps characterize the sedative-hypnotic toxidrome associated with these drugs.

However, limited pharmacokinetic data on designer benzos makes it difficult to correlate drug concentrations with specific adverse effects. Dose-response relationships, duration of action, metabolism, and onset of effects remain poorly understood, increasing the risk of accidental overdose for users attempting to self-dose. The slow elimination and active metabolites of some DBZDs (like flubromazolam and phenazepam) can lead to accumulation and delayed toxicity with repeated use. Overlapping blood concentrations in impaired and non-impaired drivers, and in DUID cases and fatalities, suggest tolerance plays a significant role. Polydrug use is a major confounding factor, often making it impossible to isolate the specific contribution of a single DBZD in fatalities. Conversely, many individuals using DBZDs may not experience significant adverse events, further complicating risk assessment. Under-detection of DBZDs due to limitations in analytical methods or lack of awareness is a significant concern. Cross-reactivity with standard benzodiazepine immunoassays and metabolism into regulated BZDs can lead to misinterpretations in toxicology findings. The role of DBZDs in deaths is complex and requires careful case-by-case assessment, considering circumstances, tolerance, and post-mortem drug redistribution. The data presented here aims to inform the interpretation of DBZD-related incidents and to educate law enforcement, clinicians, and emergency personnel about the dangers of designer benzos.

4. Materials and Methods

The review process began by identifying 31 designer benzodiazepines through consultations with international early warning systems like the UNODC Early Warning Advisory, the European Database on New Drugs, the US National Poison Data System, and the Japanese Data Search System for NPS. A comprehensive literature search was then conducted using PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Web of Science databases to locate scientific reports on emergency department admissions, DUID cases, and fatalities associated with these DBZDs. Search terms included keywords related to acute effects, abuse, emergency department access, adverse effects, diversion, driving under the influence, fatalities, illegal markets, intoxication, misuse, overdose, poisoning, reports, scheduling, seizures, and trafficking, combined with the names of the 31 selected DBZDs. Additional studies and reports were sourced from reference lists and international organizations like WHO, EMCDDA, DEA, and FDA. The review included English language articles and one Swedish article, covering data up to March 2021. Relevance screening was independently performed by one author.

5. Conclusions

The designer benzo epidemic is a growing public health and social crisis. Clinical and forensic toxicologists, working with public health agencies, are crucial in identifying emerging DBZDs in intoxication cases, drug offenses, and unexplained deaths. Reducing the time between the emergence of new DBZDs, formal notification, and international scheduling decisions is essential to curb their availability in illicit drug markets. Further research, professional training, and the development of improved analytical methods are needed to address underreporting and undercounting of DBZD-related incidents, ensuring more robust epidemiological data and effective public health responses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.H. and F.P.B.; investigation, P.B.; data curation, P.B. and M.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B.; writing—review and editing, P.B., M.A.H. and F.P.B.; supervision, R.G. and A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was partially funded by the Italian Presidency of Ministers Council, Department of Antidrug Policy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[List of references as in original article]

Associated Data

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.