Introduction

Benzodiazepines (BZDs), introduced to the US market in 1960 with chlordiazepoxide as the first approved medication, rapidly became favored over older treatments like barbiturates due to a perceived safer profile, notably reduced respiratory depression.1,2 This initial perception of safety contributed to their widespread use and acceptance in clinical practice for anxiety, insomnia, and other conditions.

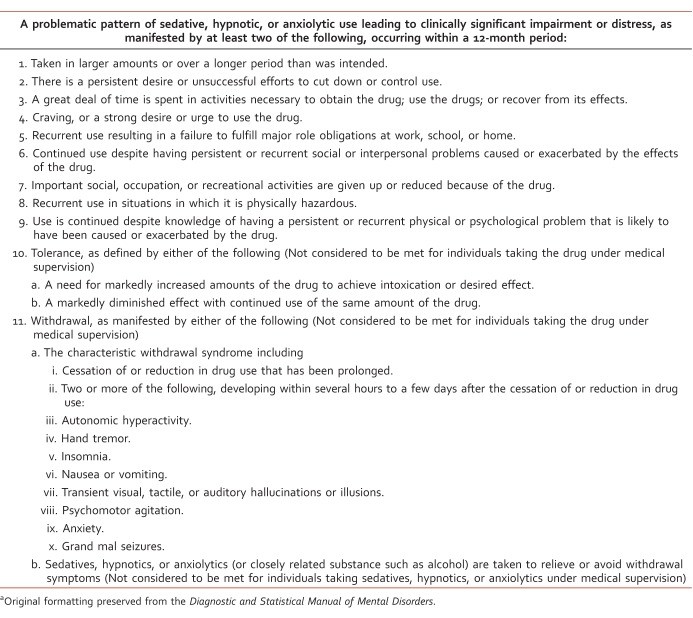

Around two decades after their introduction, the mechanism of action of benzodiazepines was elucidated. It was discovered that BZDs enhance the effect of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter, by facilitating its binding to the GABAA receptor. This interaction increases chloride ion flow through ligand-gated chloride channels, leading to a calming and sedative effect.3 Simultaneously with the understanding of their pharmacological action, clinicians began to observe and document cases of benzodiazepine abuse and dependence.1 The diagnostic criteria for sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic use disorder, which includes Benzo Abuse, are detailed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), as shown in Table 1.4

TABLE 1: .

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, diagnostic criteria for sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic use disordera

Despite the long-standing recognition of the addictive potential of benzodiazepines, significant gaps remain in our understanding of how to identify individuals at heightened risk of developing benzo addiction and the most effective strategies for treating benzo abuse. While prescription drug abuse has garnered increased attention in recent years, much of the research focus has been on prescription opioid abuse, often overshadowing the risks associated with benzodiazepines. Despite the well-documented risks of abuse and the development of safer alternatives for many conditions, benzodiazepines remain among the most frequently prescribed medications worldwide.5 This highlights the ongoing need for awareness and education regarding benzo abuse.

Prevalence of Benzo Abuse

In 2008, approximately 75 million prescriptions for benzodiazepines were issued in the United States alone, underscoring their widespread use.5 Studies indicate that the general population prevalence of benzodiazepine use ranges from 4% to 5%.5,6 Notably, benzodiazepine usage increases with age, and women are prescribed these medications approximately twice as often as men.5,7 Furthermore, individuals already prescribed opioids are significantly more likely to also receive a benzodiazepine prescription, raising concerns about polysubstance use and increased risks.7,8

While the majority of individuals who are prescribed benzodiazepines take them as directed, a concerning minority, less than 2%, escalate their dosage to high levels, and an even smaller percentage meet the rigorous diagnostic criteria for benzo abuse or dependence.9,10 In the general population without pre-existing substance use disorders, benzodiazepines are considered to have a relatively low potential for abuse.11 However, a specific subset of individuals faces a significantly elevated risk of benzo abuse, particularly those with a personal or family history of substance use disorders.12 Benzo abuse can manifest in two primary patterns: deliberate or recreational abuse, where the intention is to achieve a “high,” and unintentional abuse, which originates from legitimate medical use but progresses into inappropriate and harmful use over time.13

Benzodiazepine misuse and abuse are increasingly recognized as a significant public health problem. Estimates suggest that between 2.3% and 18% of adults in the United States have misused sedatives or tranquilizers, including benzodiazepines, for nonmedical purposes at some point in their lives.14–16 Alarmingly, nearly 10% of these individuals meet the criteria for benzo abuse or dependence.14 In 2010 alone, it was estimated that there were 186,000 new cases of benzo abusers in the US.17 Emergency departments (EDs) have witnessed a dramatic 139% surge in benzodiazepine-related visits, indicating the growing severity of the issue.18 Studies have shown that older age and the concurrent use of other drugs are associated with more severe outcomes in benzo-related emergencies, including increased risk of death.19 Furthermore, admissions to substance abuse treatment programs for benzo abuse nearly tripled between 1998 and 2008, while overall substance abuse treatment admissions only increased by 11% during the same period, highlighting the disproportionate rise in benzo abuse.20

Risk Factors for Benzo Abuse

The risk factors associated with benzo abuse and the demographic characteristics of this population exhibit notable differences compared to other substance abuse populations. Firstly, a predominant racial group identified in benzo abuse is non-Hispanic white. The role of gender in benzo abuse is less clear, as studies vary in their findings regarding the predominant gender in benzo abuse populations.15,16,20–22 Young adults, aged 18 to 35 years, constitute the largest segment of benzo abusers.20,21

A strong association exists between benzo use, misuse, and abuse and co-occurring psychiatric disorders, as well as a personal or family history of substance use disorders.12,15,23,24 Comorbid psychiatric disorders are even more prevalent among benzo abusers than in individuals abusing other substances.20,21 Approximately 40% of individuals struggling with benzo abuse also report a comorbid psychiatric disorder, emphasizing the critical need for clinicians to address both the underlying mental health condition and the benzo abuse simultaneously.20 Individuals with a history of alcohol abuse or dependence and antisocial personality disorder appear to be at a particularly elevated risk of benzo abuse compared to those without these conditions, or even those with alcohol abuse or dependence alone but without antisocial personality disorder.22 These factors highlight the complex interplay of mental health and substance use in the context of benzo abuse.

Polysubstance Abuse and Benzo Abuse

Benzo abuse frequently occurs in conjunction with the abuse of other drugs. In most cases of polysubstance abuse, benzodiazepines are secondary drugs of abuse, with a smaller proportion of individuals reporting benzodiazepines as their primary drug of abuse.20 The most common primary drugs of abuse in these polysubstance scenarios are opioids (54.2%) and alcohol (24.7%).21 It’s estimated that approximately one in five individuals who abuse alcohol also abuse benzodiazepines, highlighting the significant overlap between these two substances.22,25

Benzodiazepines are often used in combination with other substances for several reasons. These include enhancing the euphoric effects of other drugs, mitigating the unwanted side effects of other drugs such as insomnia induced by stimulants, and alleviating withdrawal symptoms from other substances.2,26,27 Individuals who abuse benzodiazepines in combination with other drugs tend to consume significantly higher doses of benzodiazepines compared to those who abuse only benzodiazepines, potentially increasing the risk of adverse outcomes.28

In 2010, benzodiazepines were implicated in 408,021 emergency department visits, representing a third of all ED visits related to pharmaceutical misuse and abuse, demonstrating the substantial impact of benzo abuse on public health resources.18 Specifically, ED visits attributed to the nonmedical use of benzodiazepines in combination with opioids have risen dramatically, from 11 per 100,000 population in 2004 to 34.2 per 100,000 in 2011. Furthermore, benzodiazepine involvement in opioid-related deaths also saw a significant increase, from 18% in 2004 to 31% in 2011. Opioids and benzodiazepines are now recognized as the two most common classes of prescription drugs involved in overdose deaths, reflecting a dangerous trend in polysubstance abuse.29 Overall death rates associated with prescription drug abuse have surged in recent years.30 Individuals who receive prescriptions for both a benzodiazepine and an opioid face a nearly 15-fold higher risk of drug-related death compared to individuals who are not prescribed either type of medication, highlighting the extreme danger of this combination.31 Admissions to treatment programs for combined opioid and benzo abuse have skyrocketed, increasing by an alarming 570% between 2000 and 2010, indicating the escalating crisis of polysubstance benzo abuse.21

Opioids are known to cause significant respiratory depression, and this effect is compounded when combined with benzodiazepines or alcohol. The interaction between opioids and benzodiazepines on respiratory function is complex. Respiration requires activation through excitatory amino acid receptors and is inhibited via GABA receptors. Respiratory control is centered in the medullary respiratory centers, which receive input from peripheral chemoreceptors sensitive to changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide levels.32 Benzodiazepines, by enhancing GABA activity, reduce respiratory motor amplitude and frequency. While benzodiazepines alone rarely cause death in overdose situations,2,12,33,34 they are relatively weak respiratory depressants on their own. However, their respiratory depressant effects become significantly more potent when used in combination with opioids.32 Opioids act on μ opioid receptors, leading to reduced sensitivity to changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations, and causing a decrease in tidal volume and respiratory rate.3,32 It is crucial to note that tolerance to opioid-induced respiratory depression develops slowly and incompletely compared to tolerance to their analgesic effects, making the combination with benzodiazepines particularly dangerous. 32

Individuals undergoing opioid replacement therapy with medications like methadone or buprenorphine are particularly vulnerable to benzo misuse and abuse.35–37 Several factors contribute to the high rates of benzo abuse in this population, including elevated levels of psychological distress, recreational drug use, sleep disturbances, attempts to minimize withdrawal symptoms, efforts to reduce negative effects of other substances like insomnia from amphetamines, and a misconception that benzodiazepines are not particularly dangerous drugs.35,36 Studies have shown alarming prevalence rates of benzo abuse in methadone maintenance patients, with lifetime benzo abuse reported at 66.3% and current abuse at 50.8%.36 Concerningly, over half of benzo users receiving methadone replacement therapy did not begin using benzodiazepines until after they had started the methadone program.38 Benzodiazepine use in combination with methadone is associated with a 60% increase in opioid-related death risk, emphasizing the grave dangers of this drug combination.39 While buprenorphine is often considered safer than methadone due to its ceiling effect, particularly regarding respiratory depression, this advantage is negated when buprenorphine is combined with benzodiazepines, eliminating the respiratory safety benefit.40 Among individuals experienced with buprenorphine, 67% reported concurrent use of benzodiazepines, and approximately one-third of these individuals obtained benzodiazepines from multiple or illicit sources, indicating a concerning trend of diversion and non-prescribed use.37

Alcohol is implicated in approximately one in four emergency department visits related to benzo abuse and in one in five benzo-related deaths, highlighting the significant role of alcohol in benzo abuse-related emergencies.18 Both alcohol and benzodiazepines act on the GABAA receptor, albeit at distinct binding sites, resulting in synergistic drug interactions. Pharmacodynamic interactions, though not fully understood in detail, lead to additive central nervous system depression, meaning that lower concentrations of each substance are needed to produce fatal outcomes when combined compared to using either substance alone.41 Benzodiazepine-related ED visits in combination with alcohol are most frequent among individuals aged 45 to 54 years, while deaths are more common in individuals 60 years and older, suggesting age-related vulnerability in alcohol and benzo polysubstance abuse.42 Despite the well-known dangers of combining alcohol and benzodiazepines, and the significant role of alcohol in various health issues, recent data indicate that only one in six adults in the United States report ever discussing their alcohol use with a healthcare professional.43 This underscores the critical need for prescribers and pharmacists to provide comprehensive education to patients about the serious risks of combining alcohol and benzodiazepines. Furthermore, healthcare professionals should proactively implement interventions and referrals when problematic alcohol consumption is suspected or identified, especially in patients prescribed benzodiazepines.

Abuse Liability of Different Benzodiazepines

Systematic studies comparing the abuse potential within the benzodiazepine class are limited. However, pharmacokinetic differences are believed to contribute to variations in abuse liability among different benzodiazepines. Lipophilicity, a chemical property influencing the speed at which a drug crosses the blood-brain barrier, is a key factor in determining onset of action.44 Benzodiazepines with higher lipophilicity and shorter half-lives appear to have a greater potential for abuse due to their rapid onset of action and shorter duration of effects, which can reinforce repeated use.11,13 Table 2 illustrates the chemical properties of several common benzodiazepines, including lipophilicity and half-life.44

TABLE 2: .

Comparison of benzodiazepinesa

Evidence from laboratory studies assessing subjective and reinforcing effects, clinical experience reported by medical professionals, testimonies from drug abusers, and epidemiological studies collectively suggests that diazepam exhibits the highest abuse liability among benzodiazepines.45 Studies evaluating subjective ratings of “high” in known drug abusers have shown that diazepam, alprazolam, and lorazepam received the highest ratings compared to oxazepam, clorazepate, and chlordiazepoxide, which appear to have lower abuse potential.2,11,45,46 In blinded studies, recreational drug users perceived diazepam to be more desirable and valuable than equipotent doses of alprazolam and lorazepam, further supporting its higher abuse potential.47

However, despite these findings, alprazolam and clonazepam are the two benzodiazepines most frequently associated with abuse-related emergency department visits. The rate of alprazolam involvement is more than double that of clonazepam, indicating a significant public health concern related to alprazolam abuse.48 Alprazolam is also the most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine in the United States. In 2009, over 44 million alprazolam prescriptions were dispensed, nearly twice the number of clonazepam prescriptions, which was the second most prescribed benzodiazepine in the US at that time. This high prescribing volume and ease of access likely contribute to alprazolam’s prominent role in benzo abuse statistics.49 While pharmacokinetics and drug preferences among individuals with substance use disorders play a significant role in abuse potential, prescribing patterns and the overall availability of specific benzodiazepine agents likely play an equally, if not more, important role in driving benzo abuse trends.50

Implications for Health Care Professionals in Addressing Benzo Abuse

Sources of prescription drug diversion are diverse and can originate from both healthcare-related and non-healthcare-related avenues. The most frequently reported healthcare source of benzodiazepine diversion is a regular prescriber, followed by “script doctors” (providers who sell prescriptions), doctor shopping (patients seeking multiple prescriptions from different providers), and pharmacy diversion (e.g., undercounting pills by pharmacy staff, employee theft).51 Recommendations for healthcare professionals to identify high-risk individuals and mitigate benzo abuse include: obtaining a thorough personal and family history of substance use, conducting urine drug screens when appropriate, frequent monitoring for signs of benzo abuse, regularly reassessing the risks and benefits of ongoing benzodiazepine therapy, prescribing a limited number of “as-needed” doses to reduce the risk of physiological dependence, and carefully differentiating between physiological dependence and true addiction.12

“Pharmacy shoppers,” defined as individuals receiving the same benzodiazepine prescription at two different pharmacies within a 7-day period, are at a 5.2 times greater risk of escalating to high doses of benzodiazepines compared to other long-term benzodiazepine users, highlighting the importance of monitoring pharmacy fill patterns.9 “Doctor shoppers,” or individuals visiting four or more clinicians within a 6-month period, are more likely to be female and have twice the risk of drug-related death compared to non-shoppers. Similarly, “pharmacy shoppers,” defined as individuals who fill controlled substance prescriptions at four or more pharmacies within 6 months, have a 3 times higher risk of drug-related death compared to non-shoppers.31,32 Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) are valuable tools in assisting healthcare professionals to identify and address prescription drug abuse, including benzo abuse.

Alarmingly, over 90% of unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities exhibit at least one indicator of substance abuse. These indicators include a known history of substance abuse, any evidence of drug diversion, nonmedical routes of drug administration, receiving controlled substances from more than five prescribers, contributing alcohol or illicit drug use, a previous history of overdose, and current opioid replacement therapy.33 Both prescribers and pharmacists must be keenly aware of these risks, utilize prescription drug monitoring programs effectively, accurately identify individuals at risk of or engaging in drug abuse, and take appropriate actions to mitigate these risks. Additional strategies to reduce benzo abuse include limiting the prescribed dose, quantity, and number of refills for each prescription.52 Drug diversion is most prevalent among young adults, who often obtain diverted medications from peers or family members, emphasizing the need for education and secure medication storage within households.8,33,52

Past attempts to reduce and restrict benzodiazepine prescribing, such as the implementation of triplicate prescription programs in New York in 1989, have had mixed results. While these programs, like the triplicate prescription system requiring copies for the prescriber, pharmacy, and state, and limiting prescriptions to a 30-day supply with no refills for most indications,53 were successful in reducing overall benzodiazepine prescribing, they also had unintended negative consequences. These stringent requirements disproportionately reduced prescribing to low-income and minority populations and led to a greater reduction in appropriate prescribing for legitimate medical needs. Such restrictive measures can inadvertently impede access to necessary medications for appropriate medical use.53–56 Healthcare providers and lawmakers must exercise caution when implementing laws and strategies aimed at tackling prescription drug abuse to avoid hindering appropriate patient care and creating disparities in access.

Some clinicians argue that the medical community may have overreacted to the risks of benzo abuse, potentially leading to underprescribing of a safe and effective class of medications. They advocate for responsible but continued benzodiazepine prescribing when clinically indicated.57 While benzodiazepines do carry abuse potential, particularly in populations with substance use disorders, it is crucial to balance these risks with the therapeutic benefits they offer. Prescribers must carefully weigh the risks of untreated underlying illnesses, such as anxiety and insomnia. Poorly managed or untreated anxiety or insomnia can, paradoxically, increase the risk of alcohol relapse and other negative health outcomes.58 Evidence-based pharmacotherapy and the use of agents with lower abuse potential should be considered first-line treatments when appropriate. However, benzodiazepines may still be indicated for certain patients, even those at elevated risk of abuse, in specific clinical situations. When benzodiazepines are prescribed to higher-risk patients, it is imperative to provide thorough patient education on the risks of combining these medications with alcohol or other substances, discuss the risks of diversion, consider prescribing benzodiazepines with lower abuse potential if clinically suitable, closely monitor for adverse effects, and vigilantly monitor for any signs of inappropriate use or benzo abuse.

Conclusion: Addressing the Challenge of Benzo Abuse

Prescription drug abuse has reached epidemic proportions, and current efforts to mitigate associated morbidity and mortality have not yet been sufficiently successful, as rates continue to rise. Further research is urgently needed to gain a deeper understanding of the risk factors for benzo abuse and to develop more effective prevention and treatment strategies. Despite the acknowledged risks of abuse and diversion, benzodiazepines remain a valuable and effective class of medications when used appropriately and continue to play a role in therapy for various conditions. Lawmakers and healthcare professionals face the ongoing challenge of reducing benzo abuse while ensuring continued accessibility for patients who genuinely benefit from these medications. Efforts should focus on reducing inappropriate prescribing practices rather than broadly restricting all benzodiazepine prescribing. Education is paramount in addressing benzo abuse. Healthcare professionals must stay informed about current abuse patterns and drug diversion trends. It is crucial for prescribers and pharmacists to educate patients not only about the risks to themselves but also the risks of medication sharing to others, to reduce diversion and misuse. Identifying benzo abuse risk factors prior to prescribing, utilizing safer alternatives when available, and implementing timely and appropriate interventions are critical steps in combating the growing problem of benzo abuse. Furthermore, expanding the availability of substance abuse treatment programs and increasing funding for these essential services will be a vital component in effectively addressing this escalating public health crisis.

Footnotes

Disclosures: This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Fargo Veterans Affairs Health Care System. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.