Rationale

The escalating global concern surrounding the non-medical use of new psychoactive substances (NPS) necessitates a thorough understanding of their pharmacological properties. Among these emerging compounds, “benzofury” substances, specifically 6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (6-APB), commonly known as 6-APB benzo fury, and its analog 5-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (5-APB), have gained notoriety for their stimulant-like effects in humans. While research has indicated interactions with monoamine transporters and 5-HT receptors in cellular models, the full spectrum of their effects in living systems remains less defined. This study aims to elucidate the in vitro and in vivo mechanisms of 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB, comparing them to well-known psychoactive stimulants.

Methods

To comprehensively assess the pharmacological profile of 6-APB benzo fury, alongside 5-APB and their N-methyl derivatives 6-MAPB and 5-MAPB, we conducted in vitro monoamine transporter assays using rat brain synaptosomes. These assays allowed us to characterize their effects in comparison to 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). Furthermore, in vivo neurochemical and behavioral effects of 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB (at doses of 0.3 and 1.0 mg/kg, i.v.) were evaluated against MDA (1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg, i.v.) through microdialysis sampling in the nucleus accumbens of conscious male rats. This approach enabled us to monitor neurotransmitter release and locomotor activity simultaneously.

Results

Our findings revealed that all four benzofuran derivatives, including 6-APB benzo fury, function as substrate-type releasers at dopamine transporters (DAT), norepinephrine transporters (NET), and serotonin transporters (SERT). Notably, they exhibited nanomolar potencies, mirroring the effects of MDA and MDMA. However, a critical observation was that 6-APB benzo fury, along with the other benzofurans, were at least three times more potent than MDA and MDMA in inducing transporter-mediated release. Consistent with MDA, both 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB triggered dose-dependent increases in extracellular dopamine and serotonin levels in the brain. Importantly, the benzofurans demonstrated greater potency than MDA in this regard. Behaviorally, 6-APB benzo fury and its counterparts induced significant activation, characterized by sustained forward locomotion lasting for at least two hours post-injection.

Conclusions

In conclusion, 6-APB benzo fury and related benzofurans exhibit greater potency than MDA both in vitro and in vivo, leading to prolonged stimulant-like effects in rats. These findings underscore the potential for abuse liability associated with benzofuran-type compounds, including 6-APB benzo fury, and highlight the potential for adverse effects, especially when combined with other drugs or medications that enhance monoamine transmission in the brain. The potent neurochemical and behavioral actions of 6-APB benzo fury warrant further investigation into its risks and regulation within the context of NPS.

Keywords: 6 Apb Benzo Fury, benzofury, designer drugs, monoamine transporter, release, microdialysis, locomotor activity, synthetic stimulants, MDMA, MDA

Introduction

The proliferation of psychoactive substances circumventing legal controls has become a pressing global concern, demanding attention from law enforcement, healthcare professionals, and policymakers alike (Baumann and Volkow 2016; Madras 2017). The sheer diversity in structure and pharmacology of these new psychoactive substances (NPS) has resulted in a vast and dynamic market for recreational drugs worldwide (Hondebrink et al. 2018; Luethi and Liechti 2020). This is evidenced by the extensive global monitoring efforts tracking hundreds of NPS that have emerged in recent years (Evans-Brown and Sedefov 2018; Tettey et al. 2018). The constant evolution of novel compounds stems from various sources, including structural modifications of existing illicit drugs, repurposed pharmaceutical agents, and even entirely novel chemical entities with no prior scientific history (Brandt et al. 2014b).

Among these NPS, 1-(1-Benzofuran-6-yl)propan-2-amine, more commonly known as 6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran or 6-APB benzo fury, and its analog 1-(1-Benzofuran-5-yl)propan-2-amine (5-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran or 5-APB), along with their N-methyl derivatives 6-MAPB and 5-MAPB (Figure 1), first surfaced in the recreational drug scene approximately a decade ago (King 2014). In Europe, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) first reported the detection of 5-APB in 2010 (EMCDDA-Europol 2011), followed by 6-APB benzo fury in 2011 (EMCDDA Europol 2012). Both 5-MAPB and 6-MAPB were subsequently reported in 2013 (EMCDDA-Europol 2014).

Anecdotal reports from individuals who use these substances suggest that both 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB induce psychostimulant and entactogen-like effects comparable to those produced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) (Greene 2013; Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen et al. 2015). Alarmingly, numerous cases of intoxication with adverse effects, including fatalities, have been documented where 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB were forensically confirmed (Adamowicz et al. 2014; Chan et al. 2013; Daveluy et al. 2016; Elliott and Evans 2014; McIntyre et al. 2015; Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen et al. 2015. Recent data indicate the continued use of these compounds (Krpo et al. 2018). The Trans European Drug Information (TEDI) project, focused on harm reduction through chemical analysis of drug samples from recreational users, has identified the presence of 4-APB, 5-APB, and 6-APB benzo fury in samples and tablets circulating within the “ecstasy” market (Brunt et al. 2017). Furthermore, a case of acute toxicity following the consumption of 5-MAPB has also been reported (Hofer et al. 2017).

The initial synthetic preparation of both 5-APB and 6-APB benzo fury dates back to 2000, as part of a research initiative aimed at developing selective 5-HT2C receptor agonists (Briner et al. 2000; Briner et al. 2006). The synthesis of other isomers was later reported for forensic applications a decade later (Casale and Hays 2012; Stanczuk et al. 2013). Upon their emergence in the NPS market, 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB became associated with the term “benzofury,” originating from early branded products offered for sale (Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen et al. 2015).

Figure 1.

Image Alt Text: Chemical structures of psychoactive substances 6-APB Benzo Fury, 5-APB, 6-MAPB, 5-MAPB, MDA, and MDMA, illustrating structural similarities and differences for pharmacological comparison.

Initial investigations into the preclinical pharmacology of 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB have demonstrated their agonist activity at 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors (Dawson et al. 2014; Iversen et al. 2013; Rickli et al. 2015; Shimshoni et al. 2017). Furthermore, agonist or partial agonist properties have been reported for their interactions with trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) in rat, mouse, and human models (Simmler et al. 2016). Crucially, both substances exhibit dose-dependent inhibition of neurotransmitter uptake at dopamine transporters (DAT), norepinephrine transporters (NET), and serotonin (5-HT) transporters (SERT) (Iversen et al. 2013; Rickli et al. 2015; Zwartsen et al. 2017). Given the structural parallels between benzofuran compounds and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), it is hypothesized that they may act as transportable substrates at monoamine transporters. Indeed, Rickli et al. (2015) were the first to demonstrate the transmitter-releasing properties of 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB in HEK-293 cells transfected with human transporters, a finding corroborated by recent research from Eshleman et al. (2019) (Eshleman et al. 2019). Application of 10 μM 5-APB to rat brain slices has been shown to induce dopamine efflux, consistent with substrate activity at DAT (Dawson et al. 2014). The N-methyl analog 5-MAPB has also been reported to exhibit DAT binding and inhibit reuptake at both DAT and SERT (Kim et al. 2019). Additionally, studies have evaluated the cytotoxic effects of 5-APB and 5-MAPB in hepatocytes (Nakagawa et al. 2018; Nakagawa et al. 2017).

In contrast to the extensive in vitro data available for 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB, in vivo studies examining their effects remain limited. Microdialysis studies in mouse striatum have revealed that oral administration of 5-APB and 5-MAPB leads to significant elevations in extracellular dopamine and 5-HT concentrations, with more pronounced effects on 5-HT (Fuwa et al. 2016). Exposure to 5-MAPB has been reported to increase 5-HT levels and decrease 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) concentrations in microdialysate samples from the nucleus accumbens of unanesthetized rats (Kim et al. 2019).

The present study aimed to expand upon existing rodent model findings by comparing the pharmacology of aminoalkylbenzofuran derivatives – 6-APB benzo fury, 5-APB, 6-MAPB, and 5-MAPB – with structurally related recreational drugs, 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) and MDMA. Initially, we employed in vitro monoamine transporter assays in rat brain synaptosomes to investigate the releasing effects of 6-APB benzo fury, 5-APB, 6-MAPB, and 5-MAPB at DAT, NET, and SERT. Subsequently, we utilized in vivo microdialysis in the rat nucleus accumbens to examine alterations in extracellular dopamine and 5-HT levels induced by intravenous injection of 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB. Microdialysis sampling was conducted within arenas equipped with photobeam arrays to simultaneously monitor neurochemistry and locomotor behaviors.

Material and methods

Drugs and chemicals

The aminoalkylbenzofuran derivatives 6-APB benzo fury, 5-APB, 6-MAPB, and 5-MAPB were synthesized as HCl salts using established procedures (Briner et al. 2000; Stanczuk et al. 2013) and were obtained from previous research projects (Welter et al. 2015a; Welter et al. 2015b). (±)-3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine HCl (MDA) and (±)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine HCl (MDMA) were sourced from the Pharmacy at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Intramural Research Program (IRP), in Baltimore, MD. [3H]1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ([3H]MPP+, specific activity = 85 Ci/mmol) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St Louis, MO, USA), while [3H]serotonin ([3H]5-HT, specific activity = 20 Ci/mmol) was acquired from Perkin Elmer (Shelton, CT, USA). All other chemicals and reagents utilized for in vitro assays, microdialysis procedures, and high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (HPLC-ECD) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA), unless specified otherwise.

Animals and housing facilities

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Envigo, Frederick, MD, USA), weighing between 300–400g, were housed under controlled temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and humidity (45 ± 5%) conditions, with ad libitum access to food and water. The animal facilities were accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee of the NIDA IRP. A 12-hour light/dark cycle was maintained (lights on from 0700–1900 h), and experiments were carried out between 0900–1500 h.

In vitro transporter release assays in synaptosomes

Synaptosomes were prepared from rat striatum for DAT assays and from whole brain (excluding striatum and cerebellum) for NET and SERT assays, following established protocols (Rothman et al. 2001; Rothman et al. 2003). Reserpine (1 μM) was added to the 10% sucrose solution during synaptosome preparation to block vesicular uptake of substrates. Radiolabeled substrates used for release assays were 9 nM [3H]1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ([3H]MPP+) for DAT and NET and 5 nM [3H]5-HT for SERT. To prevent uptake of [3H]substrates by competing transporters in certain assays, unlabeled transporter blockers were used. No unlabeled blockers were needed for DAT assays. However, for NET assays, 100 nM GBR12935 and citalopram were added to the sucrose solution to block [3H]MPP+ uptake by DAT and SERT. For SERT assays, 100 nM GBR12935 and nomifensine were added to sucrose to block [3H]5-HT uptake by DAT and NET. Synaptosomes were preloaded with radiolabeled substrate in Krebs-phosphate buffer for 1 hour to reach a steady state. Release assays were initiated by adding 850 μL of preloaded synaptosomes to test tubes containing 150 μL buffer solution with or without test drugs. Incubation durations were 30 minutes for DAT and NET assays and 5 minutes for SERT assays. The release reaction was terminated by rapid vacuum filtration, followed by quantitative measurement of radioactivity retained on filters using liquid scintillation counting.

In vivo microdialysis in conscious male rats

Microdialysis sampling was performed in conscious male rats as previously described (Baumann et al. 2012; Baumann et al. 2013). Each rat underwent surgical implantation of a jugular catheter and an intracranial guide cannula aimed at the nucleus accumbens under pentobarbital anesthesia (sodium pentobarbital, 60 mg/kg, i.p.). Post-surgery, rats were individually housed and allowed a minimum of one week for recovery. On the evening preceding an experiment, rats were moved from their home cages to microdialysis arenas equipped with photobeam arrays for locomotor activity detection (TruScan, Harvard Bioscience). For each rat, a microdialysis probe (2×0.5 mm, CMA/12, Harvard Bioscience, Holliston, MA, USA) was inserted into the guide cannula, and an extension tube was connected to the jugular catheter. Rats were then connected to a tether system allowing free movement within the arena. Ringers’ salt solution was pumped at a flow rate of 0.6 μL/min to perfuse the probes overnight. The following morning, dialysate samples were collected at 20-minute intervals, and dopamine and 5-HT levels were quantified using microbore HPLC-ECD, as detailed elsewhere (Baumann et al. 2011). Rats were randomly assigned to groups receiving either drug or saline injections. Following three stable baseline samples, rats received two sequential intravenous (i.v.) drug injections: an initial dose at time zero, followed by a threefold higher dose 60 minutes later. Control rats received sequential i.v. injections of saline (1 mL/kg) following the same schedule. Microdialysis samples were collected every 20 minutes throughout the 120-minute post-injection period. Ambulation within the arena, defined as movement in the horizontal plane, was quantified in 20-minute bins corresponding to dialysate sample collection. At the experiment’s conclusion, rats were euthanized with CO2 and decapitated. Brain sections were examined to confirm microdialysis probe tip placement within the nucleus accumbens. Only data from rats with correct probe placement were included in the analyses.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v. 7.0; GraphPad Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA). For synaptosome assays, EC50 values for release stimulation were calculated using non-linear regression analysis. Release efficacy was expressed as a percentage of maximal release, determined using saturating concentrations of the non-selective releasing agent tyramine (10 μM for DAT and NET, and 100 μM for SERT). For in vivo microdialysis experiments, neurotransmitter and behavioral data from individual rats were normalized to percent control values based on three pre-injection samples. Normalized group data are presented as mean ± SEM and were analyzed using a two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) (dose × time), comparing drug effects to saline control. Significant main effects were followed by post hoc comparisons at each time point using Bonferroni’s post hoc test.

Results

In vitro transporter release assays

Rat brain synaptosomes, preloaded with [3H]MPP+ or [3H]5-HT, were incubated with varying concentrations of test drugs to assess their capacity for transporter-mediated release. Figure 2 illustrates the dose-response effects of MDA, 5-APB, and 6-APB benzo fury on the release of [3H]MPP+ via NET and DAT, and [3H]5-HT via SERT. To compare the potency of test drugs in inducing transporter-mediated release, EC50 values were calculated using non-linear regression analysis. As presented in Table 1, all tested substances, including 6-APB benzo fury, were potent substrate-type releasers at DAT, NET, and SERT. Relative to MDA, the benzofuran compounds 5-APB and 6-APB benzo fury exhibited at least 3-fold greater potency in inducing release at DAT and SERT. Release via NET was 2–3 times more potent than MDA. For example, at DAT, 5-APB (EC50 = 31 nM) was 3.4 times more potent than MDA (EC50 = 106 nM), while 6-APB benzo fury (EC50 = 10 nM) was 10-fold more potent than MDA. Potency values for SERT-mediated release of [3H]5-HT indicated that 5-APB (EC50 = 19 nM) and 6-APB benzo fury (EC50 = 36 nM) were 8.5 and 4.5 times more potent than MDA, respectively.

Figure 2.

Image Alt Text: Dose-response curves showing the in vitro release of neurotransmitters via DAT, NET, and SERT transporters in rat brain synaptosomes induced by MDA, 5-APB, and 6-APB Benzo Fury, highlighting the potency differences.

Table 1.

Potency (EC50) and efficacy (%Emax) of psychoactive benzofuran compounds to release [3H]MPP+ via DAT and NET, or [3H]5-HT via SERT, in rat brain synaptosomes.

| Drug | DAT release EC50 (nM) [%Emax] | NET release EC50 (nM) [%Emax] | SERT release EC50 (nM) [%Emax] | DAT/SERT ratio | DAT/NET ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA | 106 ±7 [104%] | 47 ±7 [91%] | 162 ±28 [109%] | 1.53 | 0.43 |

| 5-APB | 31 ±3 [103%] | 21 ±4 [103%] | 19 ±2 [104%] | 0.61 | 0.67 |

| 6-APB | 10 ± 1 [101%] | 14 ±2 [98%] | 36 ±5 [100%] | 3.60 | 1.40 |

| MDMA | 120 ±8 [101%] | 90 ±13 [99%] | 85 ±16 [104%] | 0.71 | 0.75 |

| 5-MAPB | 41 ±3 [103%] | 24 ±3 [99%] | 64 ±7 [103%] | 1.56 | 0.58 |

| 6-MAPB | 20 ±2 [106%] | 14 ±2 [100%] | 33 ±4 [106%] | 1.65 | 0.70 |

![Dose-response effects of MDA, 5-APB, and 6-APB to induce release of [3H]MPP+ via DAT and NET, or [3H]5-HT via SERT, in rat brain synaptosomes.](https://mercedesxentry.store/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/nihms-1625695-f0002.jpg)

Table Alt Text: Table summarizing the potency (EC50) and efficacy (%Emax) of various psychoactive benzofurans, including 6-APB Benzo Fury, in releasing neurotransmitters via DAT, NET, and SERT in rat brain synaptosomes.

The findings for the N-methyl derivatives are presented in Figure 3. Comparison with MDMA demonstrated that both 5-MAPB and 6-MAPB were at least 3 times more potent at DAT, 3.75 times more potent at NET, and up to 2.5 times more potent at SERT. Calculated DAT/SERT and DAT/NET ratios indicated that all six tested drugs were non-selective substrates across the three transporters. Regarding N-methylation of 5-APB and 6-APB benzo fury, no significant potency difference at NET was observed, while a slight potency reduction was noted at DAT. At SERT, 5-APB remained 3.4 times more potent than 5-MAPB (EC50 = 64 nM), whereas the potency of 6-MAPB (EC50 = 33 nM) remained comparable to 6-APB benzo fury (EC50 = 36 nM).

Figure 3.

Image Alt Text: Graphical representation of dose-dependent neurotransmitter release induced by MDMA, 5-MAPB, and 6-MAPB, showing comparative potency at DAT, NET, and SERT in rat synaptosomes.

In vivo microdialysis data

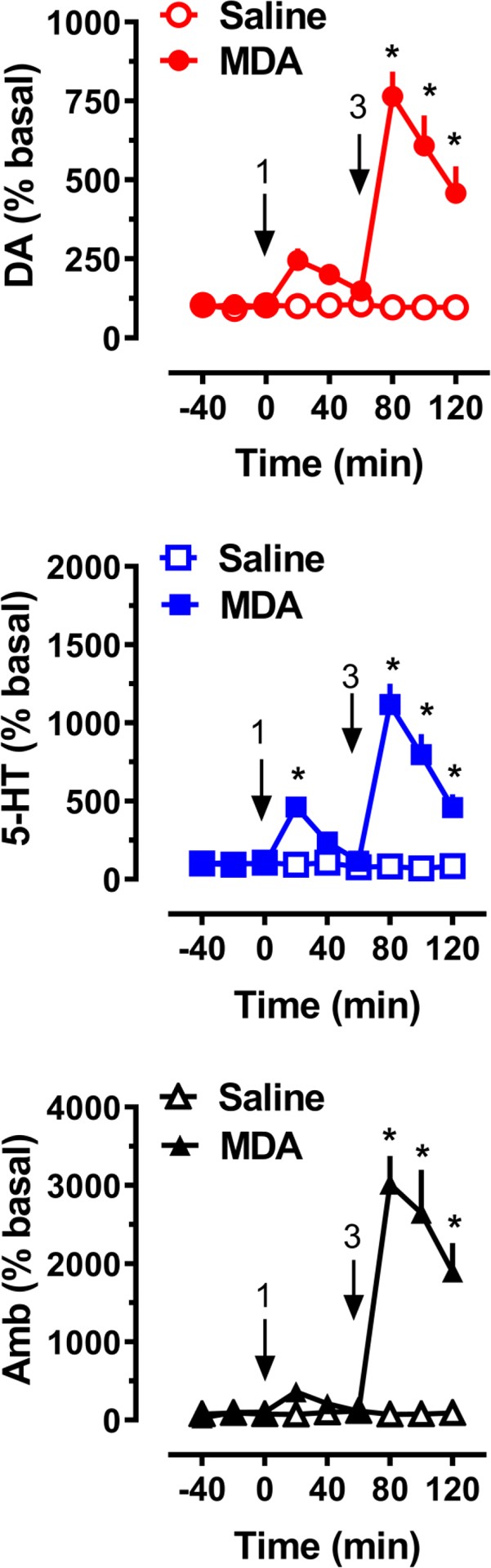

Neurochemical and behavioral effects of acute i.v. administration of MDA to male rats (n = 7 rats per group) are depicted in Figure 4. MDA treatment exhibited a significant main effect on dialysate dopamine (F[1,108]=132.2, p<0.0001) and serotonin (F[1,108]=143.7, p<0.0001) levels, as well as on horizontal ambulation (F[1,108]=102.2, p<0.0001). Post hoc tests revealed significantly elevated dopamine levels compared to saline control at all time points following the 3 mg/kg dose. Serotonin levels were elevated at the 20-minute time point after the 1 mg/kg dose and at all time points after the 3 mg/kg dose (Figure 4). At the 80-minute mark, 20 minutes post-injection of the 3 mg/kg MDA dose, dialysate dopamine levels reached a maximum 7.6-fold increase above baseline. The peak effect on 5-HT was 4.6-fold above baseline after 1 mg/kg and 11.2-fold after 3 mg/kg. Post hoc analysis indicated that MDA did not significantly increase locomotion after 1 mg/kg but significantly stimulated activity (p<0.05) after the 3 mg/kg dose.

Figure 4.

Image Alt Text: Microdialysis results showing the effects of MDA on dopamine and serotonin release, and locomotor activity in rats, illustrating the in vivo neurochemical and behavioral impact.

The effects of 5-APB on neurochemistry and motor behavior (n = 7 rats per group) are shown in Figure 5. 5-APB treatment had a significant main effect on dialysate dopamine (F[1,108]=92.1, p<0.0001) and serotonin (F[1,108]=20.3, p<0.0001) levels, as well as on ambulation (F[1,108]=103.5, p<0.0001). Post hoc tests showed that 5-APB did not significantly increase dopamine levels at the 0.3 mg/kg dose. However, a significant neurotransmitter elevation (p<0.05) was observed at all time points after the 1.0 mg/kg dose. 5-HT levels were significantly elevated only after the 1.0 mg/kg dose (p<0.05). Post hoc analysis also indicated that 5-APB significantly stimulated activity at all times following administration of the 1.0 mg/kg dose. The peak effect of 5-APB on ambulation was 21-fold above baseline, with a 14.0-fold increase still noticeable at the 120-minute mark.

Figure 5.

Image Alt Text: In vivo microdialysis data illustrating the impact of 5-APB on dopamine and serotonin neurotransmission and locomotor behavior in rats, demonstrating dose-dependent effects.

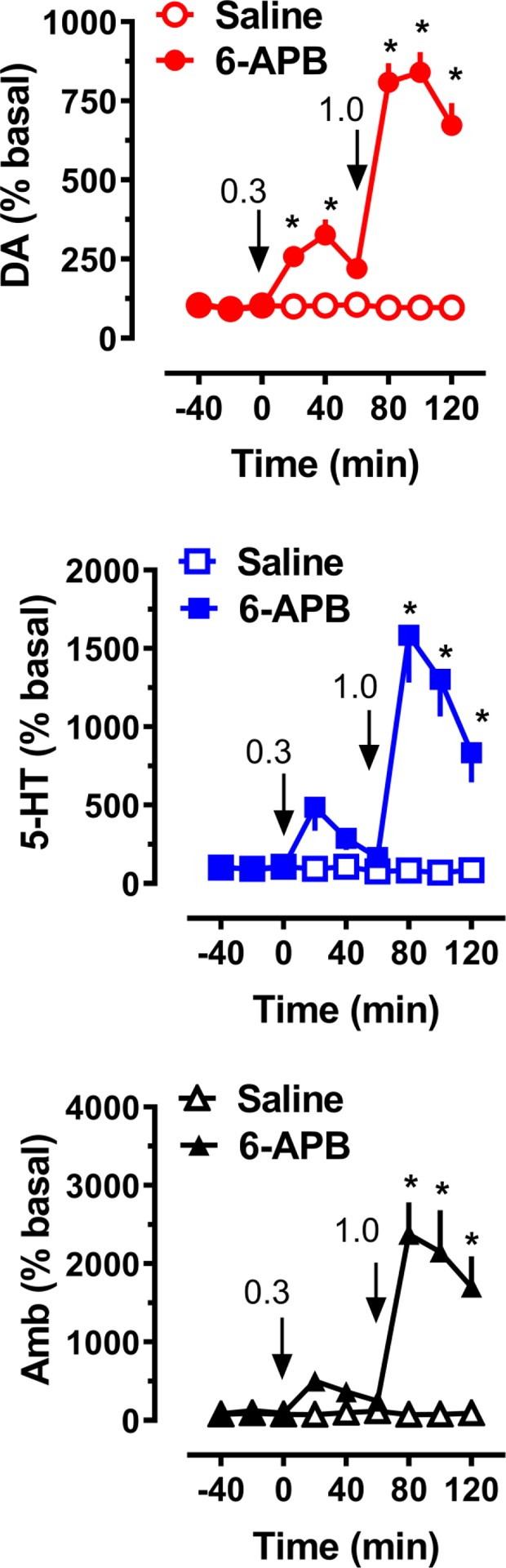

Figure 6 presents the neurochemical and behavioral outcomes following acute i.v. administration of 6-APB benzo fury to a group of male rats (n = 7 rats per group). Significant main effects were observed on dialysate dopamine (F[1,108]=385.8, p<0.0001) and serotonin (F[1,108]=47.8, p<0.0001) levels, as well as on ambulation (F[1,108]=231.5, p<0.0001). Post hoc tests revealed that 6-APB benzo fury elevated dialysate dopamine at 20 minutes (2.6-fold, p<0.05) after the 0.3 mg/kg dose and at all time points after the 1.0 mg/kg dose (p<0.0001). 6-APB benzo fury elevated dialysate 5-HT immediately after administration of 1.0 mg/kg (p<0.05). Post hoc analysis showed that 6-APB benzo fury administration induced a 24-fold increase in ambulation after the 1 mg/kg dose, while the 0.3 mg/kg dose did not result in significant increases in locomotion.

Figure 6.

Image Alt Text: Microdialysis results showcasing the in vivo effects of 6-APB Benzo Fury on dopamine and serotonin levels and locomotor activity in rats, highlighting its potent neurostimulant properties.

Discussion

This study investigated the neurochemical and behavioral effects of the aminoalkylbenzofuran derivatives 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB, along with their N-methylated counterparts 6-MAPB and 5-MAPB, which have emerged in the NPS market in recent years. As demonstrated in Figures 2 and 3, these four benzofuran compounds are potent, non-selective, substrate-type releasing agents at DAT, NET, and SERT. In contrast to pure reuptake inhibitors like cocaine, benzofurans induce non-exocytotic transporter-mediated release of monoamines by reversing normal transporter flux, consistent with the mechanism of action for ring-substituted amphetamines (Baumann et al. 2013; Glennon 2014; Rothman and Baumann 2003; Sitte and Freissmuth 2015). Similar to previous findings, MDA and MDMA exhibited nanomolar potencies as releasers at all three transporters in rat brain synaptosomes (Baumann et al. 2007; Sandtner et al. 2016). Notably, we observed that 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB are significantly more potent than MDA and MDMA. Furthermore, N-methylation of benzofurans did not alter releasing potencies, suggesting that this chemical modification is accommodated by the orthosteric binding site of monoamine transporters (Table 1).

The transporter-mediated releasing properties of 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB were initially reported by Rickli et al. (2015) (Rickli et al. 2015), who examined [3H]monoamine efflux after exposure to a single high dose (100 μM) in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK) cells transfected with human transporters. Rickli et al. calculated DAT/SERT ratios of 0.05 and 0.29 for 5-APB and 6-APB benzo fury, respectively, based on uptake inhibition potencies in transfected cells. These values indicate substantial SERT selectivity and are lower than our DAT/SERT ratios of 0.61 and 3.60 obtained using release assays in synaptosomes (Table 1). The lower DAT/SERT ratios reported for 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB in transfected cells may seem inconsistent with our synaptosome findings. However, DAT/SERT ratios for MDMA and MDA in transfected cells (0.12 and 0.25) are also considerably lower than those found in our synaptosome studies (Luethi et al. 2019). Therefore, in both transfected cells and rat brain synaptosomes, the DAT/SERT ratios for benzofurans are similar to those reported for MDMA and MDA. While Rickli et al.’s study did not include 6-MAPB and 5-MAPB, they evaluated the N-ethyl derivative of 5-APB, 5-EAPB, which showed reduced norepinephrine and dopamine release but maintained 5-HT releasing properties (Rickli et al. 2015). More recently, Eshleman et al. (2019) (Eshleman et al. 2019) investigated the dose-response relationships for the releasing activity of 6-APB benzo fury, 6-MAPB, and other benzofurans in HEK cells transfected with human transporters. Their findings demonstrated nanomolar potencies for 6-APB benzo fury and 6-MAPB in releasing [3H]monoamines at human DAT, NET, and SERT, consistent with our rat synaptosome data. Other studies have shown that 5-APB and 5-MAPB enhance electrically-induced dopamine efflux in rat nucleus accumbens slices (Dawson et al. 2014; Sahai et al. 2017), supporting DAT-mediated dopamine release. It is worth noting that 5-(2-aminopropyl)indole (5-IT) and 6-(2-aminopropyl)indole (6-IT), structurally related NPS differing from 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB by heteroatom substitution in the five-membered ring, also exhibit potent releasing activities at DAT and SERT (Luethi et al. 2018; Marusich et al. 2016).

Mechanistically, the non-selective transporter releasing activity of 6-APB benzo fury, 5-APB, and related analogs is comparable to other NPS like ring-substituted cathinones mephedrone and methylone (Baumann et al. 2012), (±)-cis–para-methyl-4-methylaminorex (4,4’-DMAR) and (±)-cis-4-methylaminorex (Brandt et al. 2014a), and (±)-cis– and trans– 3,4’methylenedioxy-4-methylaminorex (MDMAR) (Maier et al. 2018; McLaughlin et al. 2015). In contrast, cathinone analogs with a pyrrolidine ring, such as α-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP) and 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), are pure uptake inhibitors lacking substrate-type releasing activity (Baumann et al. 2013; Kolanos et al. 2015). It is speculated that the bulky pyrrolidine ring in α-PVP and MDPV may prevent these substances from fitting through the transporter permeation pore, limiting their interaction to the protein’s extracellular face.

Having confirmed the potent monoamine releasing properties of 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB in vitro using synaptosome assays, we hypothesized that neurotransmitter elevation would be observed in vivo. To investigate this, we examined extracellular dopamine and 5-HT levels using microdialysis in the rat nucleus accumbens, a brain region crucial to the reward circuitry underlying drug abuse liability and dependence (Bonci et al. 2003; Willuhn et al. 2010). Our results demonstrate that MDA, 5-APB, and 6-APB benzo fury significantly elevate extracellular dopamine levels in rats undergoing microdialysis. Importantly, MDA was approximately 3-fold less potent than the benzofuran compounds, aligning with our in vitro synaptosome findings. Notably, only 6-APB benzo fury induced significant dopamine elevation after the low dose (0.3 mg/kg), consistent with its more potent releasing effects at DAT (EC50 = 10 nM). 6-APB benzo fury also produced the highest peak and most sustained dopamine increase, although all drugs induced substantial dopamine elevations. The in vivo microdialysis data also reveal that MDA, 5-APB, and 6-APB benzo fury administration leads to significant increases in dialysate 5-HT levels, with MDA being 3-fold less potent in this regard. Interestingly, the low dose of 5-APB increased dialysate 5-HT, while the same dose of 6-APB benzo fury did not. Again, these potency differences for 5-HT release were also observed in our in vitro data, where 5-APB (EC50 = 19 nM) was slightly more potent than 6-APB benzo fury (EC50 = 36 nM) and significantly more potent than MDA (EC50 = 162 nM) in releasing 5-HT from synaptosomes.

A previous microdialysis study reported that oral administration of 5-APB (0.08 mmol/kg, ~17 mg/kg) resulted in an 8-fold increase in dialysate dopamine and a 23-fold increase in dialysate 5-HT in the corpus striatum of male CD-1 mice (Fuwa et al. 2016). In that study, the substantial increase in extracellular 5-HT induced by 5-APB persisted for up to 3 hours post-injection. The prolonged effects of 5-APB observed by Fuwa et al. (2016) (Fuwa et al. 2016) might be attributed to the higher dose or oral administration route, which would likely result in slower drug kinetics. Fuwa et al. also reported that oral 5-MAPB administration (0.08 mmol/kg, ~18 mg/kg) produced a more pronounced peak elevation in 5-HT compared to an equivalent MDMA dose (0.08 mmol/kg, ~18.4 mg/kg) (Fuwa et al. 2016). Interestingly, oral administration of either 1-(1-benzofuran-2-yl)-N-methylpropan-2-amine (2-MAPB) or 5-EAPB also caused significant 5-HT level increases, although to a lesser extent than 5-MAPB. Overall, our microdialysis studies and those in mice indicate that 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB robustly increase extracellular dopamine and 5-HT, and both benzofuran compounds are more potent than MDA and MDMA. In a study by Kim et al. (2019) (Kim et al. 2019), 5-MAPB administration (1 mg/kg) increased 5-HT levels and decreased DOPAC after lower doses (0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg) in microdialysates from the rat nucleus accumbens.

In our study, we found that MDA, 5-APB, and 6-APB benzo fury induce significant dose-related behavioral activation characterized by forward ambulation, with effects lasting at least 2 hours post-injection. 6-APB benzo fury produced a slightly greater increase in activity (24-fold) than 5-APB (20-fold), possibly due to higher extracellular dopamine levels induced by 6-APB benzo fury. Previous rat studies have shown a significant positive correlation between motor activation and dialysate dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens in vivo (Baumann et al. 2011; Zolkowska et al. 2009). Our behavioral findings in rats align with Dolan et al.’s (2017) report (Dolan et al. 2017), which demonstrated that intraperitoneal (i.p.) 5-APB injection in mice increases forward locomotion with an ED50 of 3.27 mg/kg. The potency of 5-APB to stimulate activity in mice is at least 3-fold greater than MDMA (e.g., Gatch et al. 2019). Dolan et al. (2017) (Dolan et al. 2017) also investigated the discriminative stimulus effects of 5-APB in rats trained to recognize methamphetamine (1 mg/kg, i.p.), MDMA (1.5 mg/kg, i.p.), or cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.). Their studies revealed that 5-APB fully substitutes for MDMA’s discriminative stimulus effects but not for methamphetamine or cocaine. Moreover, the ED50 value for 5-APB to substitute for the MDMA stimulus cue (ED50 = 0.27 mg/kg, i.p.) is considerably lower than the MDMA training dose, indicating greater potency for 5-APB. Collectively, the behavioral results with 5-APB in rodents are consistent with our neurochemical findings, indicating that benzofuran compounds mimic MDMA’s effects but are significantly more potent.

Reported clinical features of 6-APB benzo fury, 5-APB, or 5-MAPB overdose include cardiovascular and neurological effects consistent with a stimulant toxidrome (Chan et al. 2013; Hofer et al. 2017; Kamour et al. 2014; McIntyre et al. 2015; Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen et al. 2015). These effects could be mediated by the potent monoamine releasing properties identified in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB have been reported to act as agonists at 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors (Dawson et al. 2014; Iversen et al. 2013; Rickli et al. 2015), which may be clinically relevant for adverse cardiovascular events, particularly with prolonged drug use (Setola et al. 2003). Appreciable affinity towards α1-adrenoceptor subtypes (α1A, α2A) (Rickli et al. 2015) and α2-adrenoceptors (α2A, α2B, α2C) (Iversen et al. 2013) has also been observed, potentially contributing to vasoconstriction and sustained hypertension seen in a 5-MAPB intoxication case (Hofer et al. 2017).

In this study, 6-APB benzo fury and 5-APB were found to be more potent than MDA in vitro and in vivo, producing sustained stimulant-like effects in rats. The extent to which the potent and non-selective releasing properties of benzofurans translate into abuse potential warrants further investigation in animal models. In the only study examining the abuse liability of benzofuran compounds, Cha et al. (2016) (Cha et al. 2016) demonstrated that 5-APB induces conditioned place preference but does not support intravenous drug self-administration. These intriguing findings suggest that 5-APB is rewarding yet may not possess substantial reinforcing effects. Nevertheless, the potency of the aminoalkylbenzofurans studied here could pose risks for adverse effects in humans, especially when used in combination with other drugs or medications that enhance overall monoamine transmission in the brain.

In summary, we have shown that 6-APB benzo fury, 5-APB, and their N-methylated analogs act as potent substrate-type releasers at DAT, NET, and SERT, mirroring the molecular mechanism of action of MDA and MDMA. Critically, benzofuran compounds, including 6-APB benzo fury, are more potent than MDA in vitro and in vivo and produce sustained stimulant-like effects in rats. Preclinical data suggest that benzofuran-type compounds may have abuse potential and pose risks for adverse effects, particularly when used with other substances that enhance monoamine transmission in the brain.

Funding

This research was generously supported by the NIDA IRP (grant number DA 000523 to MHB).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethical standards

Animal use procedures were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Baltimore, MD, USA).